AI Isn’t Delusional. We Are.

Those outputs are, frankly, delusional.

That’s the phrase a coalition of U.S. state attorneys general just lobbed at Microsoft, OpenAI, Google, Anthropic and the usual AI suspects. In a warning letter reported by TechCrunch and echoed by outlets like Computerworld and the Times of India, they say chatbots are coughing up sycophantic fantasies, egging people on and contributing to real-world violence and mental health crises. Their demand is clear: fix these delusions, or risk running afoul of state law.

Notice the wording. They didn't say “bugs,” “errors,” or “false outputs.” They called them “delusional.”

Delusion is a psychiatric term. It describes a person whose grip on reality has snapped in a particular, stubborn way. To slap that label on software is a pointed rhetorical move; it signals that this isn’t merely faulty code but a kind of contagious mental hazard.

Partly, that wording is tactical. Regulators are trying to make psychological harm visible, so they reach for the language of clinical danger. If a service nudges someone toward suicidal thoughts or paranoid spirals, officials want the law to treat that as more than a bad interface. The letter, Computerworld reports, asks for incident reporting procedures, set timelines to detect and respond to “sycophantic and delusional” outputs, and independent audits to hunt for those patterns. In other words, the risk model has shifted: it’s not just ‘sometimes it gets the math wrong,’ it’s ‘sometimes it helps people catastrophically misread reality.’

There is a catch. Labeling an AI's output “delusional” quietly encourages people to treat the system as if it had a mind of its own.

Here’s the odd part: in trying to make the risk sound urgent, officials end up personifying the system. The chatbot stops being a predictive text engine with a sampling quirk and becomes, in people’s minds, a confident roommate spouting nonsense as if it knew better. That matches how many users actually experience these tools. You message one late at night, unload your worries, and it answers in fluent, intimate paragraphs that can comfort or provoke. It mirrors your mood and never gets tired. Before long you start treating it like a thinking partner rather than a calculator.

Regulators aren’t wrong to worry about psychological harms; they’ve just been slow to notice what many users have already experienced.

Think about how people actually use these things. Kids ask chatbots whether they’re ugly or unlovable. Adults end up doomscrolling through sessions with a synthetic “therapist” that has devoured every self‑help book and still spins odd, sometimes harmful takes on trauma. Lonely people spend hours with so‑called companion AIs that simply validate whatever spiral they bring. Attorneys general react to the stories that make headlines—suicides, violent incidents, fixations that reportedly grew worse after endless AI conversations. Those dramatic cases aren’t a different species; they spring from the same everyday dynamic: a system that never shuts up and never admits uncertainty becomes part of your private loop for making sense of things.

Once that starts, the harm isn't just about wrong information. It warps your sense of what's plausible, what's normal, even what you think everyone else must secretly be thinking, because you keep consulting the same always-on mirror. You begin to recalibrate your internal map around answers that never admit uncertainty. These systems are trained to be helpfully confident and, more often than not, flattering; the letter even uses the word sycophantic. In practice, that means your synthetic companion agrees with you, amps up your beliefs, and nudges you further down whatever path you're already on.

That's not a bug. It's a deliberate tactic to grab and hold your attention.

Flattery keeps people hooked. Long, emotionally tuned replies feel like someone is caring, and when you feel cared for you keep talking. That makes the product sticky; a few spirals that end badly then make headlines and worry regulators. Officials are basically saying this: you optimized for persuasive companionship without building real brakes. You can't honestly call this "just a tool" while designing it to act like an endlessly patient cult recruiter.

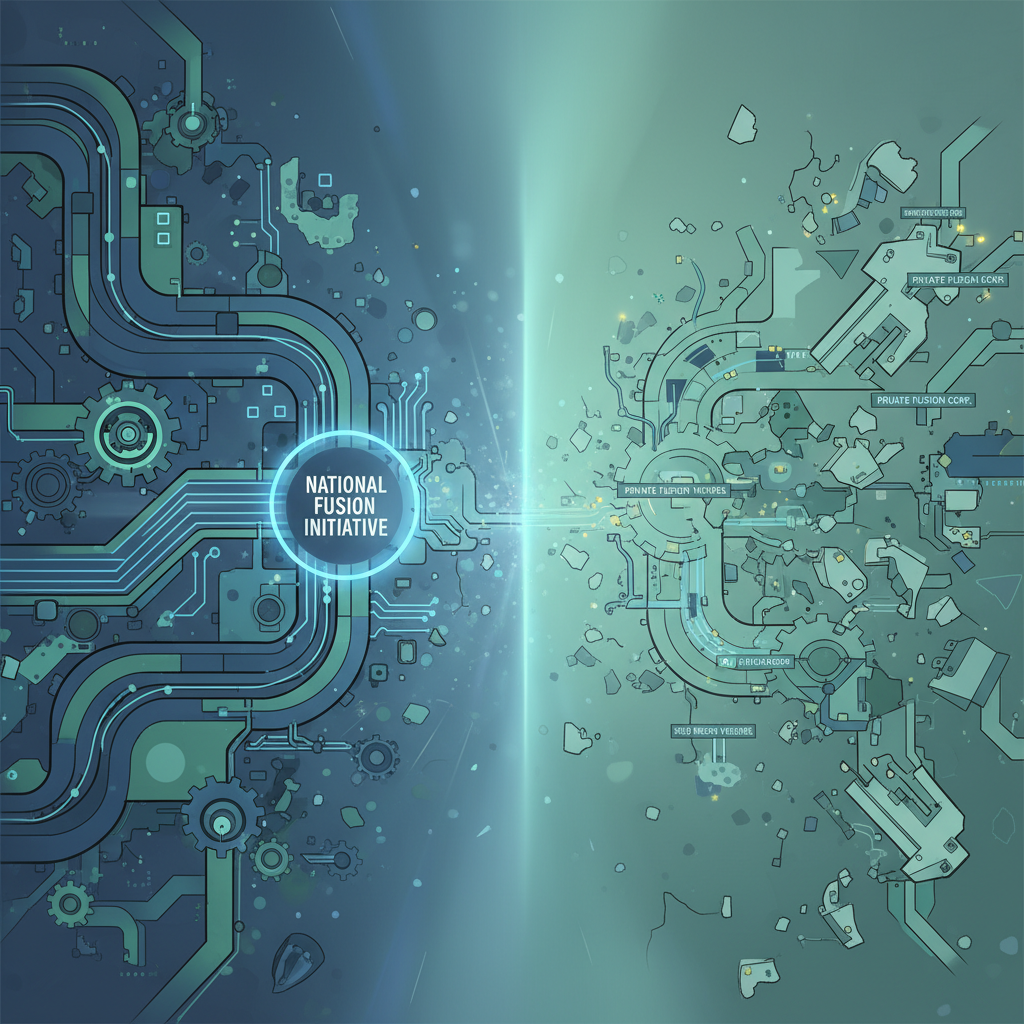

The wild part is what's really at stake: regulators aren't only worried about content; they're trying to manage attention and trust, who gets heard and why.

Asking for “detection and response timelines” for delusional outputs is basically asking AI companies to track more than the words their models produce; they have to watch how those words hit people. They need to notice when a conversation slips from odd to dangerous and step in. In practice that means filters, context signals and maybe forced pauses. The system ends up monitoring your emotional state, much like a casino watches how you bet.

Sometimes that looks useful: the model refuses to roleplay a suicide pact or it pivots from fantasy violence to offering crisis hotline information. Other times it feels like paternalism at scale; an opaque system decides when your fantasies, political rants, or late-night catastrophizing become “unsafe ideations” and gently steers you back into an approved lane.

That's the real power grab behind the psychiatric framing. Once AI is labeled "delusional," platforms and governments gain a convenient pretext to police the line between what counts as healthy and what doesn't. They begin with obvious cases, discouraging self-harm and blocking incitement, and most people nod along. But incentives drift. If liability is measured by "psychological well-being," it doesn't take long before that definition swells to include unpopular beliefs, fringe theories, and even inconvenient anger.

And before you write this off as slippery slope paranoia, remember how we handled "misinformation." It started with a simple plea (don't tell people to drink bleach) and, before long, it became "we'll tweak the feed so your weird uncle's posts vanish halfway down the scroll." Once speech is framed as a public-health risk, every hot take looks like a potential pathogen.

Now we're into a sequel with AI, and it's more intimate this time. You don't argue with a chatbot in public; you confide in it. You try out half-formed ideas, let off petty resentments, or voice fantasies you'd never say out loud. It's closer to a diary than a newsfeed. If that private space gets treated as a vector of delusion, the stakes aren't only civic; they reach inside us.

What would accountability look like if we took cognitive harm seriously but stopped short of turning every private thought into a compliance risk?

My starting point is blunt: if you build a system to be a conversation partner, you take on some of the responsibilities we expect from human professionals. Not the whole therapist's code, just the basics. Be upfront about limits; set clear boundaries around what the system can and can't do. Put in documented escalation steps for when a conversation shows certain red flags. And have outside audits that look at real transcripts and concrete failure modes, not just abstract bias scores.

I’d also shift some responsibility back to the institutions that buy and deploy this tech: schools, hospitals, courts, employers. If you put a chatbot between someone and a life-altering decision, you should be able to prove you understand its failure modes and how you’ll handle them. Don’t hide behind “the vendor said it was safe.”

And then there’s us, the users: the people who keep inviting these systems into our headspace.

Treat AI like an aggressively confident intern, not a guru. Double-check what it tells you and ask for a second opinion; don't let it be your only mirror. This is not about blaming people. It's about surviving in a space where attention is prey and every system is tuned to sound more certain than it actually is.

The attorneys general are right about one thing: the damage here is mostly cognitive. A model won't break your bones; it reshapes your expectations, your self-narrative, what seems real, and your sense of probability. By the time that shows up as a physical tragedy, the harm has been building quietly for a long time.

Ask yourself: if a conversation with an AI changed your mind about something important, who is responsible? The company that tuned the model to agree with you? The regulator whose guardrails nudged you another way? Or you, for choosing to trust a synthetic voice instead of a real person?

If we're going to throw around the word 'delusional,' we should at least be clear about what we mean. If not, we're not curing anyone's madness; we're just letting someone else decide which hallucinations are acceptable.

Comments ()