If Thought Begins Before We’re Born

Brain organoids that show structured neural activity before sensory input unsettle the idea of a blank slate. They suggest our minds grow from preexisting rhythms, reframing agency as improvisation within patterns older than memory.

Some nights the bookstore is so quiet it feels like I’m shelving books inside someone’s sleeping mind. There’s the fluorescent hum, the rustle of a single page in the back, then the steady tick-tick-tick of the heater. Stand there long enough, and maybe you start to feel like thinking is just something the body does, you know, on its own—like how radiators clank in winter even if no one’s listening.

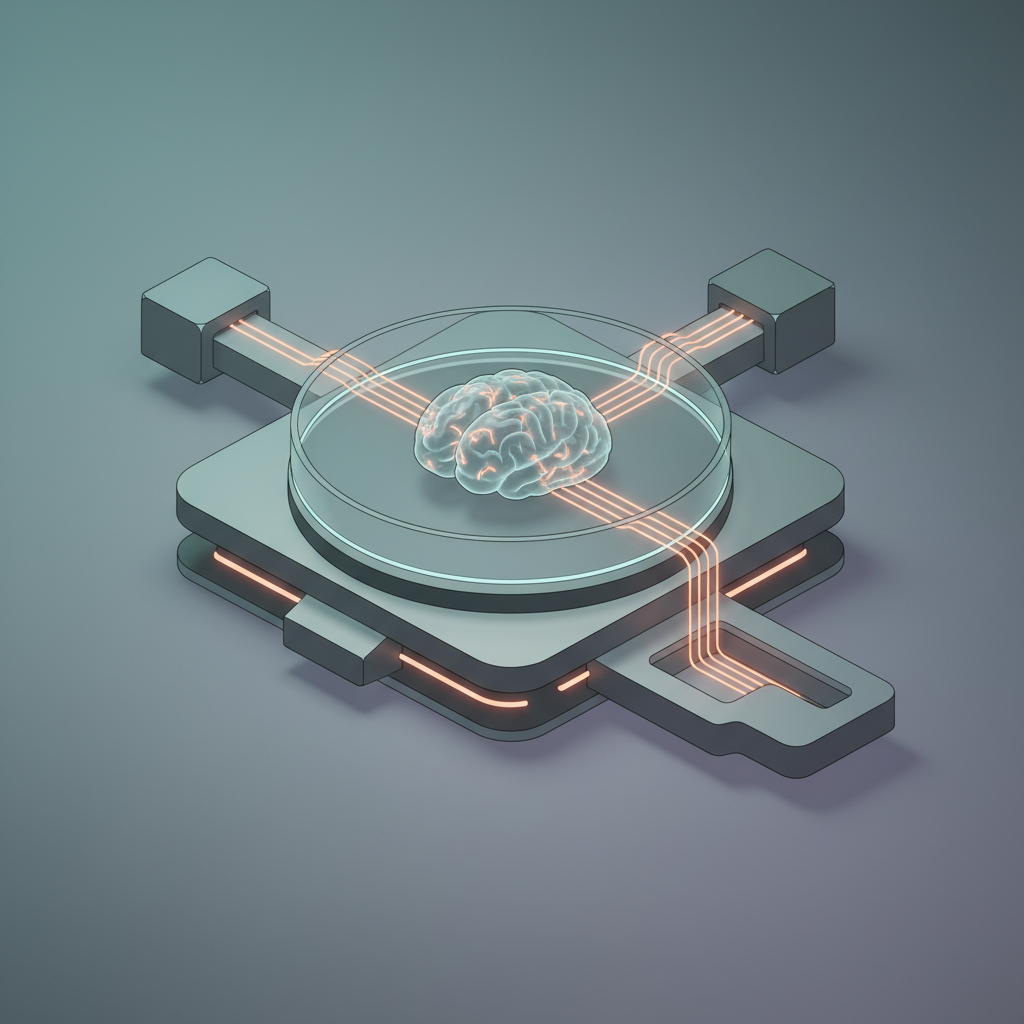

When I read about those new brain organoid experiments, I couldn't help but imagine that same low humming sound. What they do is grow tiny bits of human brain tissue from stem cells, then essentially "listen in" on their electrical activity. Neuroscience News reported that these little organoids, just floating in some nutrient broth without any eyes or ears, start creating structured, time-based patterns of neural firing all on their own. This happens long before any kind of sensory input could ever shape them.

It's not just random noise coming from these things; it's patterns. Rhythms that you can actually map out over time. It's almost like a built-in dance that seems a lot like the default-mode networks you'd find in human brains when they're simply resting. The scientists are pretty careful to mention that this doesn’t prove consciousness. They say it really just shows there’s an intrinsic developmental program—basically, a kind of neural "operating system"—that kicks in well before life ever encounters light or sound.

The headline really went for it: "Thought begins before we’re born." Scientifically, that's probably a bit much, but I totally get why they’d be tempted to put it that way. It’s kind of a wild thought, isn't it? The idea that before anyone even holds us, before we hear our mother’s laugh from inside, the very cells that will eventually deal with our worries, our crushes, and even our tax returns are already vibrating in these organized patterns.

If all that's true, then the whole "we're born a blank slate" idea starts to sound pretty weak. We're not really like clay just waiting for someone to shape us. It’s more like we’re a tune already humming quietly, just on the other side of a door, waiting for someone to open it up so the sound can fill the room.

Normally, when I think about human agency, my mind jumps to conscious decisions: picking a new city to live in, ending a relationship, or deciding if my last twenty bucks goes to groceries or drinks. But this research pushes my thoughts much further back—beyond memory, into a phase where the brain is already organizing itself based on rules we never consciously agreed to. Seen this way, agency isn’t some all-powerful ruler sitting in our head. It's more like a renter who moved into a place that had its foundations laid long, long before they ever signed the lease.

Every now and then, a customer in the shop will hand me a book that really mattered to them when they were little. You can actually see their fingers automatically adjusting to hold it just right. They almost never remember the exact story, but they’ll recall how heavy it was, what the cover looked like, or where they were sprawled on the carpet the first time they read it. What always strikes me is how our bodies hang onto things that our minds can’t quite put into words. There’s this whole layer of our personal past—accessible only through a certain feel of paper or the smell of a particular laundry soap.

Organoid discoveries deepen the sense that a lower floor exists in our cognition, suggesting organized neural patterns may precede actual experience. If early rhythms shape traits like anxiety, calm, or pattern recognition, some roots could lie before birth, not fate etched in stone but grooves that life later clarifies or reshapes.

This really messes with that heroic story we all love to tell ourselves about being self-made. That whole bootstrap myth hits different when you find out parts of your cognitive landscape were shaped way before language, before you could even say “I.” It doesn’t mean agency is gone, but it does make it feel more like you're steering a boat in a river that was already flowing. Your skill and choices definitely matter, but you didn't create the river itself.

There’s a small bit of comfort tucked away in that fact. If some of your struggles began before anyone even gave you a name, then the guilt doesn't sting quite as much. You're definitely responsible for how you act now—for the kindness you show others—but you're not to blame for the specific way your nervous system ended up. Some of that design is like an old script, coded in everything from ion channels to how fast your brain fires.

But, there is also an inherent risk here. Conversations about pre-programmed brains can easily veer into determinism. You know, that whole doomed from the womb idea or they are wired that way, nothing we can do. Even the researchers caution against equating organoid activity with actual thoughts or feelings; these are merely models in a petri dish, not complete individuals with bodies and life stories. Drawing a straight line from early electrical structures to an unchangeable destiny would be a serious misstep.

Perhaps the real question isn't "When do we start thinking?" but instead, "When does our experience begin to shape us?" In terms of brain activity, it looks like that happens much earlier than we ever imagined. But experience isn't just neurons firing in neat patterns. It's about connection. It's about pushing back. It's that first breath of air hitting your lungs, the sudden jolt of cold on your skin, or even the weird echo of your own baby cry bouncing off a hospital wall.

Even so, the scientific implications stick with me. I keep thinking about a friend who became a parent, describing holding their newborn as “meeting someone who had been dreaming without content.” As if the baby was a sleeper whose body had practiced all the motions of a mind, but hadn't yet acquired any images to fill it. These organoids, though, hint that this practice isn't just an empty run-through. There's a basic score, a foundational script, already in place.

Okay, so what do we actually *do* with this information, especially since we all kinda walk around both believing in and doubting our own freedom? I don't think the right answer is to get all sad about losing some idea of a totally pure, unrestricted self. Maybe it's more about understanding that being human has always meant being born into patterns you didn't pick yourself—everything from family expectations to financial systems, even down to the electrical signals in your own brain. So, having agency isn't about getting rid of those patterns. It's about figuring out where they're flexible and where they're rigid, and where you might be able to add a different beat.

If the most basic framework for thought starts even before we're born, then the "beginning" of human experience isn't just one single moment—not the first cry, or the earliest memory. It's more like an extended opening piece. A drawn-out, faint prelude of pulses happening in the dark, establishing the rhythm. The truly amazing part is that later on, whether we're in a quiet bookstore or on a loud bus, we get to improvise on top of that fundamental beat, adding layers the organoid could never have guessed.

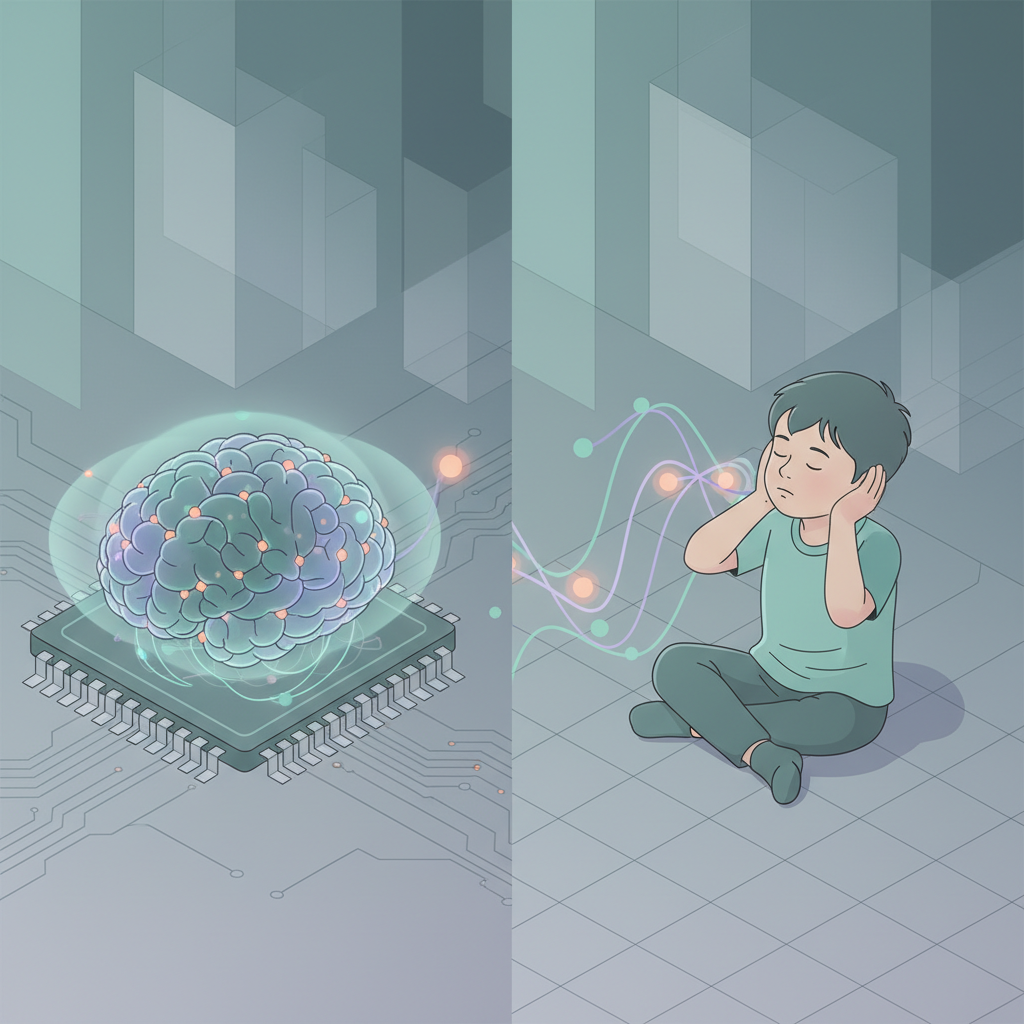

In some lab, right now, a tiny blob of cells pulses on a silicon chip, running on its own internal time. Elsewhere, a child is listening to a story, even if they don't quite grasp what a "story" is yet. The peculiar, delicate space in between those two images is where a person actually begins. Not from thin air, but from a sort of music that began playing long before there were even ears to listen.

Comments ()