The Four Ages Of The Brain, And The Selves We Keep Shedding

A new study identifies four “turning point” ages in brain wiring. From nine to thirty‑two, our brains stay adolescent; later life brings new shifts in connection and narrowing focus. I sit with what that means for how we feel ourselves changing over a life.

The whistling of the kettle stops, and the room settles into that specific kind of night-time silence. You know, when the pipes have quieted down and the street outside is more shadows than cars. I'm thirty-two, an age a bunch of Cambridge scientists and a BBC headline claim is when my brain finally shifts out of adolescence. A part of me just wants to laugh at that, honestly. Another part wonders what exactly just got its diploma.

This whole thing started with a study that analyzed brain scans from thousands of people, from birth to nearly ninety. They watched how the connections between brain cells evolved. The researchers pinpointed "turning points" in the brain's wiring—four distinct ages that jump out from the gradual changes over a lifetime: around nine, thirty-two, sixty-six, and eighty-three. They label the time before nine as childhood. From nine to thirty-two, we're neurologically considered adolescents. Then, from thirty-two to sixty-six, we're adults. Beyond that, aging happens in two phases, early and late, each bringing its own shifts in connections and losses, some brain areas chattering away while others become silent.

That initial turning point at nine keeps coming back to me. When I was nine, I was small and mostly read books, learning the school library by heart and starting to notice grown-ups told harmless lies. The Cambridge researchers say that's roughly when the brain's networks reconfigure themselves, moving from childhood's loose, exploratory layout into a more structured, effective pattern. It’s also statistically when some mental health issues start to become more common. The scientists, in their BBC interviews, made sure to emphasize these are just averages, not set fates. Still, there’s something a little unsettling about the idea that an entire brain era snaps shut while you're still practicing your times tables.

If childhood is an open field, nine is the age someone starts drawing fences. You start to grasp what embarrassment is. You learn there's a voice for inside your head and one for speaking aloud, and that some thoughts are better kept to yourself. The brain's constantly trimming and strengthening its own pathways, figuring out which routes will turn into major roads and which will return to being overgrown. No wonder memories from those years feel like a brightly lit fog; the whole system was getting rewired as we tried to make sense of things.

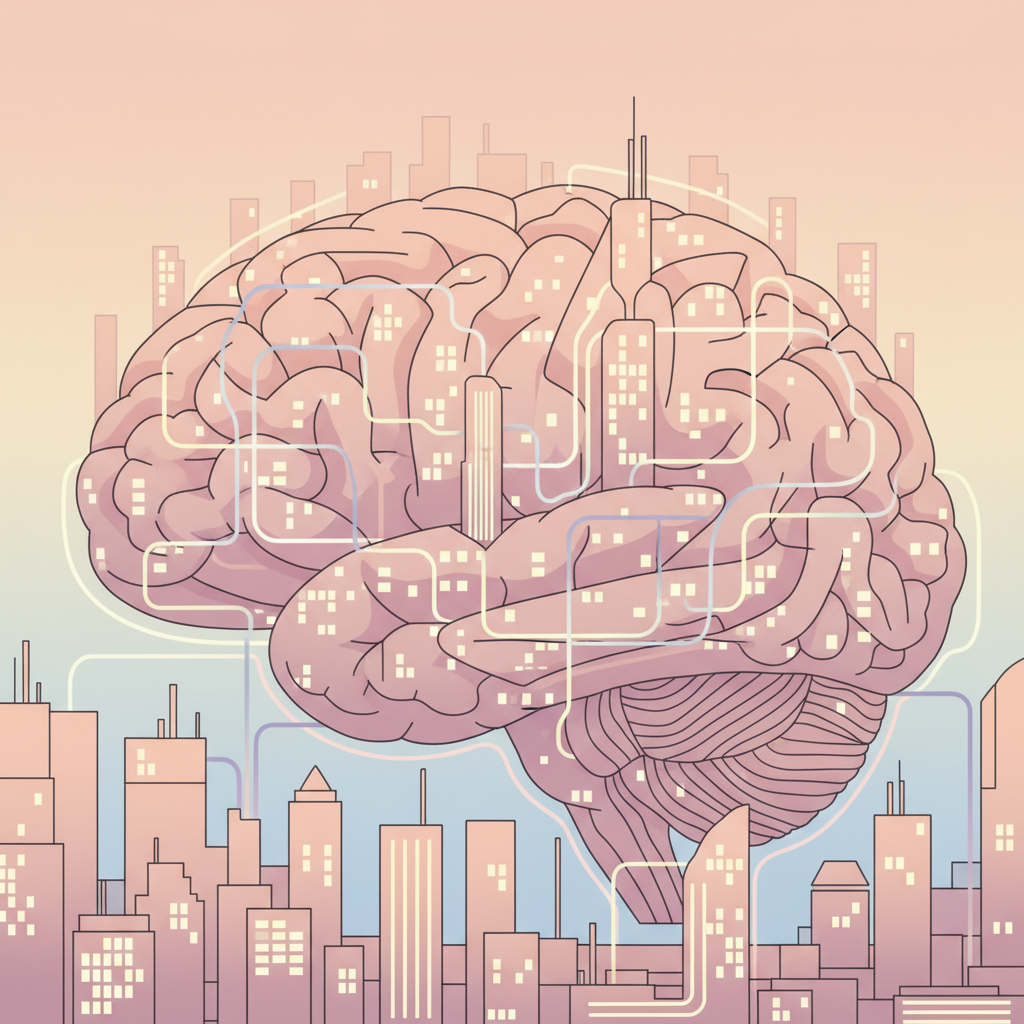

Then you have that long, flexible period from nine to thirty-two, which the study calls adolescence. National Geographic's article mentioned the lead author saying that the brain is "expected to be doing something different" at various times. During these two decades, it seems the brain is busy getting both quicker and more interconnected, tightening up localized communication between regions so we can think more effectively. When I read that, I imagine a city announcing its subway is finally running on schedule, even though it's quietly shut down all but a handful of lines.

It's a strange sort of relief to think my brain was still "adolescent" even when landlords and tax forms already considered me a grown-up. All those wandering, late-night talks in dorms, how friendships felt like parts of a shared nervous system, the absolute certainty that every heartbreak was the end of the world: maybe some of that intense feeling wasn't just me messing up. Maybe it was actually part of how a brain built for trying new things operates, still putting together and testing out different connections. Even in my late twenties, when I was stacking books during the day and trying to write poems at night that didn't make me cringe, I often felt like the basic structure of who I was was only temporary. Turns out, my brain was totally on board with that.

Okay, so at thirty-two, according to Nature Communications and what the BBC reported, the brain apparently hits what one scientist called the biggest "turning point" of your whole life. After years of specializing, this huge network of connections reaches its most efficient point. Parts of the brain that need to communicate across your head can do it fast. Information just flows smoothly. When you look at scans, it's like seeing a system that's finally found its groove. I don't really think of it as reaching the top of a mountain, though; it’s more like that moment during a really long walk when your legs just fall into a rhythm, and you suddenly realize you're not even tired anymore.

The problem with labeling something a peak is that it makes everything afterward seem like it's going downhill. At sixty-six, the study noted another change.

But when I read about those ages, my thoughts went less to illness and more to the subtle, everyday shifts I've seen in people I care about as they've moved through life. My grandmother in her late seventies, for instance, often hummed around the house, sometimes misplacing a word but never losing the thread of a story. Or there's an older regular at the bookstore who consistently returns to the same three authors, almost as if refining her taste isn't a limitation but a comforting return home. If the brain's networks are indeed becoming more internally focused and less broadly connected, maybe some of what we label as stubbornness or nostalgia is simply how that reorganization feels from the inside. It's like the mind begins to curate itself, and the world gently shrinks to what it can truly embrace.

Of course, there’s a risk in treating these averages like a strict script. Not everyone’s brain follows the exact same trajectory. Things like poverty, trauma, illness—basically all the circumstances we don't choose in life—can pull that curve in really different ways. Some folks seem old by twenty, while others stay adaptable and open-minded well into their seventies. The Cambridge team made it clear: these turning points are just markers, not checkpoints you have to hit. Still, I find myself wanting to use them as excuses. If adolescence truly stretches to thirty-two, maybe I’m not behind on anything. Maybe we've all been too quick to put an end to the process of becoming.

What really sticks with me, beyond all the charts and careful warnings, is this picture of a brain that just never stops rearranging itself. We're consistently in some stage of re-wiring, even if it slows down, even if the chatter between brain regions gets a bit quieter. The 'self' you carry around isn isn't some fixed statue. It's more like a flow of traffic, a collection of preferred paths, kind of like a city at night with only certain windows glowing. At nine, new areas light up. By thirty-two, the whole transit map might feel finished. Then, at sixty-six and eighty-three, maybe the city simply learns to manage with fewer bridges, sticking to the streets it knows best.

It makes me want to approach people—including myself tomorrow—with a sort of patient curiosity. If our minds are built with these unseen thresholds, then each age isn't just a number; it's a fresh experience of how we pay attention, what we remember, and what seems achievable. Every conversation we have is shaped by countless tiny electrical choices, influenced by a lifetime of turning points we never even noticed. This study simply puts a few birthdays on those invisible changes.

Looking out the window, the street's pretty deserted now. My tea kettle's gone cold. In a few years, some new research will probably redefine these periods, maybe add a new detail or dispute an old one, which is just how science works. But for now, I like imagining that my brain, whether it's still adolescent or not, is still doing its thing. Still figuring out how to exist right here. Still, in its own quiet, electric way, evolving into the person it's not quite finished becoming.

Comments ()