The Staring Game: When Digital Detox Becomes Social Disruption

Public transport runs on a quiet pact. People take up just enough space and keep their voices down, turning their attention to something unobtrusive. More often than not, that means scrolling a screen, paging through a book, or slipping on a pair of headphones. It feels like a form of self-containment, but it also serves as social containment, a small cocoon that makes the commute easier for everyone.

Barebacking, the device-free commute, is getting attention. No phone, no headphones, no book, no podcast; just stillness. The term comes from podcaster Curtis Morton, who framed it as a small act of defiance and pointed to an unsettling side effect: prolonged staring, deliberate eye contact, and a kind of open-faced noticing. Fortune notes that this subway habit mirrors the long-haul travel vibe—a way to reject in-transit stimulation.

The motivations seem reasonable on paper. Psychologist Danni Haig describes the practice as a quiet rebellion against overstimulation; a chance for the nervous system to settle, reduce anxiety, and sharpen focus. Career coach Amanda Augustine adds a boundary argument: with more teams returning to offices, commuters are reclaiming their commute as personal time rather than unpaid pre-work. The commute becomes a liminal zone again, not a rolling inbox.

Taken in isolation, this feels like self-care by subtraction. But in the broader system, it becomes a norm violation inside a tightly packed attention network.

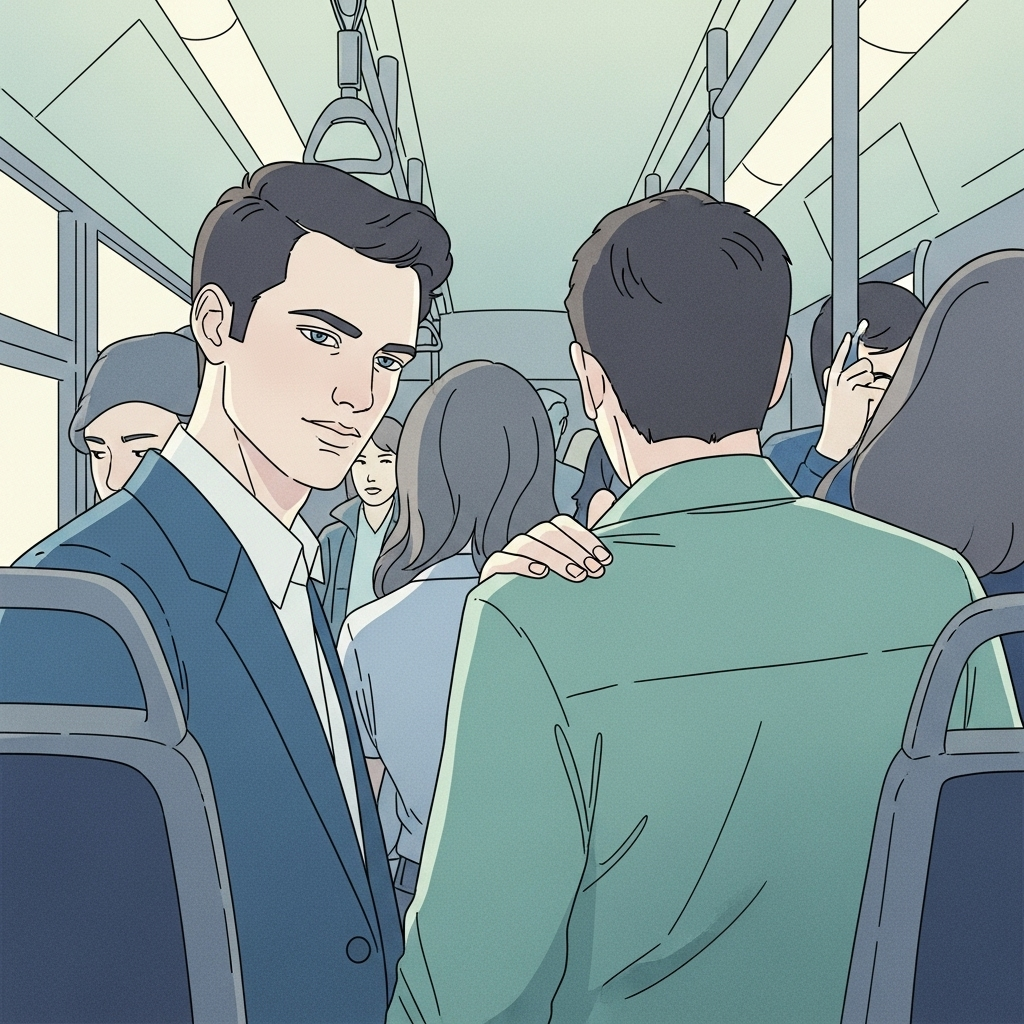

Commuting goes beyond simply getting from here to there. It feels like an attention economy. Screens, headphones, and quiet cars act as insulation, soaking up the charged proximity around us. Remove that insulation and your presence becomes noticeable. A gaze has somewhere to land, and when it lingers on someone for more than a moment, the mood changes for everyone nearby. Some riders experience that shift as a quiet threat; others as awkwardness they now have to navigate. There is a long-standing unspoken rule on buses and trains: avoid eye contact, keep as still as possible, and project a gentle disinterest.

Barebacking disrupts the choreography not because stillness is wrong, but because a calm moment with direct eye contact can feel loud in a crowded space. Even supporters acknowledge that other passengers may feel unsettled by it, especially when it turns performative; for example, in the trend’s more theatrical versions that call for looking out the window or meeting someone’s gaze as part of the act (sources: LADbible, Fortune).

I started with a personal tweak to cut down on digital overload. But the effect wasn’t just on me; the tension moved into our shared space. I feel calmer, yet the car around me now seems strange. What began as private repair has turned into a public experiment.

What looks like a small lifestyle tweak is really a clash of default settings.

That cognitive default has become our baseline. Over years of constant little nudges (notifications, background apps, brief task switches), the mind has learned to hum at a steady pace. Letting that tempo drop can feel like real relief. Haig's point about the nervous system settling rings true, especially since the commute is one of the few bounded blocks of time left in a day. The mind relaxes when we allow it to idle, and that idling is not nothing. It is consolidation, diffuse-mode processing, and recovery from screen fatigue, all of which Fortune notes can sharpen clarity later.

Public transit runs on a quiet default: we’re there, surrounded by others, yet wrapped in our own thoughts. You’re with people, but not really with them. Screens promise a closed loop, a private feed you’re meant to follow. Bare hands drift over glass, and eyes sweep the car, signaling interest or simply passing time. In close quarters, a glance can read as an invitation or an intrusion. The platform era trained us to publish our attention to feeds. On the train, that same attention, when it isn’t filtered through a device, becomes a broadcast to anyone in your line of sight.

3) The economic default. Forcing people back into the office and the habit of always-on communication have pushed more mental load into the commute. Augustine’s point isn’t a quick productivity trick; it’s a boundary diagnosis. People are redefining where work begins, and they’re using deliberate non-use as a way to reclaim time (Fortune).

Think of it as a three‑body problem: one person chasing calm, a train car crowded with others, and habits built for a different rhythm that no longer fit. The outcomes feel predictable. Fellow travelers push back to restore balance, by stepping aside, shifting seats, and offering small, irritated glances. The barebacker experiences that resistance as intolerance. Both sides act rationally within the same system, each carrying a different idea of what the commute is supposed to be for.

There are two details that will really shape how this unfolds.

Names shape behavior. When we call it 'barebacking,' we’re not just naming a practice; we’re issuing a dare. The label invites visible commitment, nudging people from private hesitation to public display, where the point isn’t merely to be with one’s thoughts but to be seen being with them. In short, personal coping can turn into a social signal once the label is in play.

Second, our attention norms are platform residue. For a decade, the daily commute trained us to fill dead zones with input; that served both the platforms and the fragile peace of public space. We outsourced awkwardness to algorithms. If a new cohort withdraws from that contract, the awkwardness returns to the room until new micro-norms emerge.

What’s happening feels bigger than a Gen Z fad. It reveals a dependency we never named aloud: we’ve been using our personal devices to regulate how crowded our attention gets. We once assumed phones wreck focus in private spaces, then forgot they can actually help steer attention in public. They act as quiet conflict dampeners. Take them away, and you’ll notice what they’ve been soaking up.

None of this argues against device-free commutes. The mental reset they offer has real value. The real question is how we design presence. Stillness doesn’t have to be socially loud. Most of the friction comes from ambiguous eye contact, not from the absence of earbuds.

When agency matters more than performance, a useful distinction to hold onto is between private attention and public attention.

Private attention is attention you direct without trying to interpret or shape how others read you. It feels like a soft glance out a window, or a moment spent on a neutral detail in the room, sometimes with the eyes gently closed. Public attention, by contrast, invites interpretation from others. It plays out as a long scan of faces, steady eye contact, or that blank stare that people feel compelled to react to. The private kind keeps you in charge; the public kind asks others to decide what to make of you.

Think of this in system terms: the goal is load management. A healthy intervention reduces total load, not merely moves it around. Quiet withdrawal can lower the overall cognitive temperature in a crowded car. If you treat it as a staring contest, you export your discomfort and call it presence.

Looking ahead, we should focus less on whether the trend continues and more on how everyday norms adjust in response. Two shifts are likely to emerge: first, a reframing of what counts as normal in light of the trend; second, new patterns of behavior that follow from that shift.

There's a new etiquette for analog idleness. The cues we relied on before smartphones (neutral eye contact and minimal movement) could be relearned now as deliberate choices rather than defaults. Expect rituals that signal focused attention without screens: eyes closed, breathwork, and even simple window gazing that feels outward, away from you.

Organizational pushback or co-option is likely. When leaders interpret device-free commutes as a rejection of pre-work, some will try to reclaim that time by adding optional morning standups or by pushing for earlier deadlines. Others will defend the boundary, arguing that time away from work supports sustainable performance. Depending on incentives, the same pattern may be labeled insubordination or simply workplace hygiene.

The underlying pattern remains unchanged: whenever people try to reclaim their attention, they do so within systems that were happily consuming it. Resistance is never spotless. It stirs something up. The real skill is figuring out whether that disturbance restores balance or simply shifts the discomfort onto someone who never asked to carry it.

Funny thing about doing nothing: the hardest part is pulling it off without bothering anyone.

Fortune's coverage on barebacking explores its connections to RTO boundaries, LADbible's reporting looks at trend dynamics and Danni Haig's perspective, and Eastern Eye summarizes the psychological benefits discussed alongside public discomfort.

Comments ()