What Binaural Beats and Boss Battle Music Teach Us About Attention

In Texas, a teenage tester ran a simple focus test with kids, feeding slightly different tones into each ear, and got results that grown-up neuroscientists are still arguing about. Binaural beats seem to help people pay attention, while video game music sometimes makes things worse. Science News for Students gave the project a cautious but impressed nod. It’s a small, messy experiment, but the pattern it hints at feels familiar: when you’re coding to a game soundtrack, your brain shifts from the debugger into boss fight mode.

To put it plainly, a handful of simple, orderly sound patterns seem to keep attention steady, while richer, more 'interesting' sounds tug focus away from the task. That contrast feels a little odd, since we tend to describe attention as a kind of heroic effort or a personal failing, not as something that can be nudged by the frequencies in our headphones.

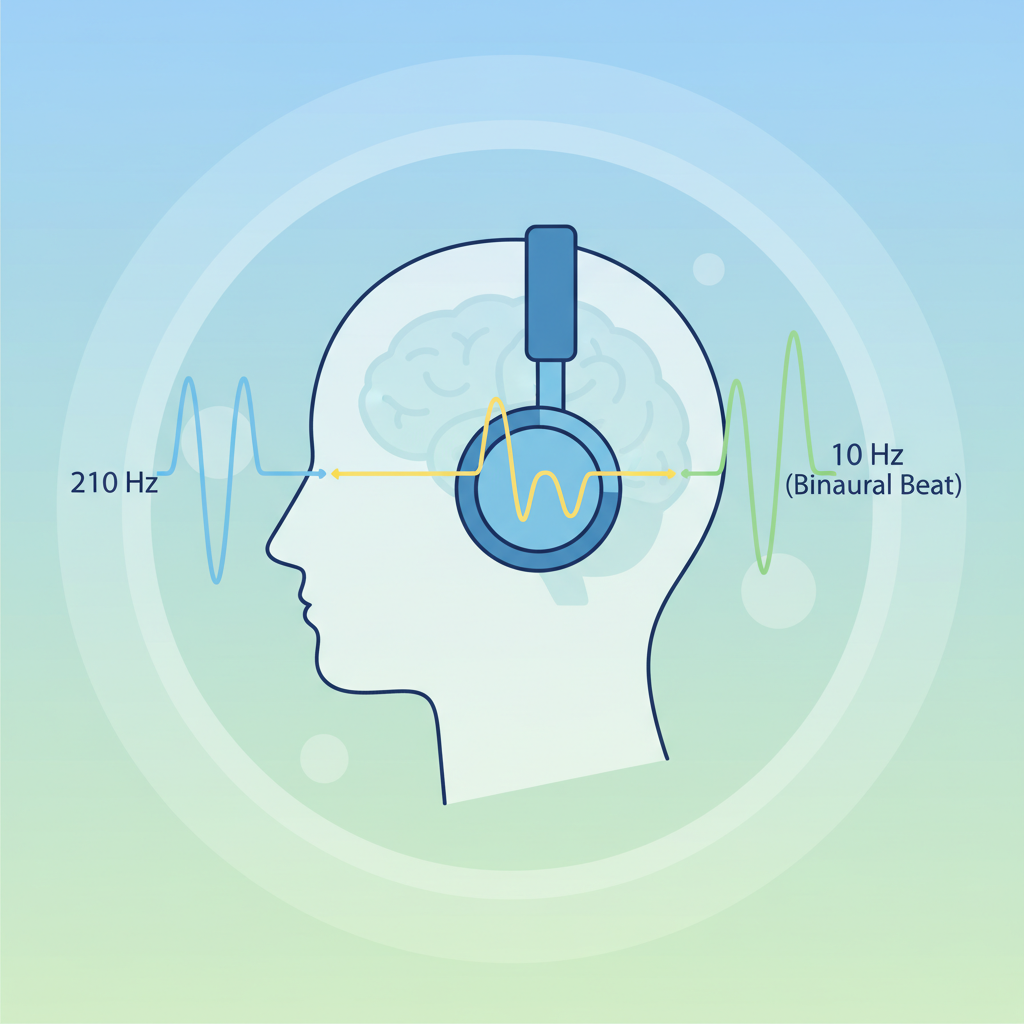

Binaural beats offer a tangible way to think about this. There’s nothing spooky going on. If you play a 210 Hz tone in the left ear and a 200 Hz tone in the right, there isn’t a 10 Hz sound in the room. Yet the brain picks up the difference and you can perceive a slow 10 Hz wobble. EEG researchers at places like the University of Nevada and others have spent years debating whether that subjective beat actually shows up as synchronized brain activity in corresponding bands. Some experiments report small increases in power or coherence in those ranges and see modest boosts on tasks that resemble sustained attention or working memory; others find little to nothing useful or even small impairments.

Science News for Students characterizes the teen’s data as sitting on the hopeful edge of the literature: participants perform an attention task, are tested under different sound conditions, and show a benefit at one beat frequency with a cost for game music. Am I convinced binaural beats are some magical 'focus hack'? Not really. The evidence is mixed, and the effect sizes, when they appear, tend to be small. But as a probe into how attention works, the idea is neatly tidy. It draws a line between a boring, structured signal that tries to entrain your timing and a richer, narrative-rich sound that asks you to follow it.

One way to picture this is to think of attention as a small set of control processes that have to decide, moment to moment, what matters. Some of those processes keep time with a rhythm. The brain's oscillatory circuits sweep like tiny radar beams, sampling sensory input in phases. If you present a highly regular stimulus, especially at a frequency that overlaps with a rhythm already guiding attention, you’re giving those circuits a clean, low-entropy reference clock. It’s a lot like slipping a metronome into a band that was already playing at roughly the same tempo.

Video game music is in a class of its own. Great game scores weave in hooks, crescendos, misdirections, and payoffs. The soundtrack signals state changes: the tension before a fight, the thrill of leveling up, the mystery of a new area. Even without lyrics, it tells a narrative. It taps into your brain’s predictive systems. You’re not just hearing a chord; you’re quietly asking, “Will this resolve here?” and “Is this looping into a new section?” That’s cognition, and it eats attentional resources.

If you’re using predictive coding as a frame, you can think of our perceptual system as constantly drafting models of what should happen next and then updating them. Simple, repetitive sounds are cheap for that system. Once it locks on, updates stay small, errors stay low, and the model hums along with little top-down input. Attention can drift elsewhere. By contrast, narrative or complex music keeps surprising you enough that the model never fully settles. Choruses, key changes, melodic motifs that hint at something and then bend the pattern, and all of that forces the system to keep recalibrating. You’re running a second task: tracking the story in the music.

There’s also the language problem. Any sound carrying meaning, lyrics most obviously but also spoken voice, lights up brain networks we rely on for school and work tasks: phonological processing, word recognition, and syntactic parsing. You can say you’re not listening to the words, but your auditory system didn’t get that memo. Studies comparing background speech with non-speech noise keep showing the same pattern: the meaningful stream is hard to ignore, even when you try. So if you layer lyrics on top of game-like dynamics, you’re almost certain to slow your task performance unless the task is trivial.

What stands out to me is that the structured sounds that help aren’t gripping in the usual sense. People don’t walk away humming a binaural beat track. If there’s any benefit, it seems to come from its lack of narrative pull. It sits just above white noise, organized enough to give your timing a scaffold, but thin enough in content that it doesn’t invite daydreaming. It’s the cognitive equivalent of choosing a background color instead of wallpaper.

That idea upends a lot of folk wisdom. We tend to equate engagement with quality in media: flashy production values, a rich story, constant novelty. Yet for certain kinds of work, what you want is the opposite: a sensory environment that cooperates with your brain's control systems rather than competing with them. A teenager inadvertently showed that a soundtrack built to juice emotional engagement in a game can become a saboteur when you drop it into a math test.

Once you admit it, you also admit that attention is something you can tune. If you can brighten or dull it with the background sounds you choose, you can treat attention as a dial on a control loop rather than a fixed character trait. That realization has two consequences. First, it's liberating. You can stop telling yourself that you’re morally weak for not being able to focus through anything. Instead, tell yourself that your environment is poorly tuned for the task you’re asking of yourself. Second, you adopt a practical approach: you run experiments on the environment first.

There's a darker side to this as well. Anything that can be tuned can be optimized, even hijacked. Once we see that certain timing patterns help keep attention on a feed, or that particular musical contours make you less likely to leave a game, those patterns stop being neutral tools and become design primitives. Social platforms already lean on similar ideas, with infinite scroll and notification sounds. Game designers have learned, from experience, how to keep people in the loop. Adding more explicit attention-entrainment tricks on top of that isn't a huge leap in concept.

That points to a future where some soundtracks genuinely help you stay focused at work, while others are sold as focus aids but quietly push you to stay attached to an app or platform. Both kinds may use regular rhythms, specific bands of frequencies, or small variations to stave off boredom. The difference comes down to what the surrounding system is optimizing for: your task completion, or someone else’s time-on-site metric.

Sometimes I picture attention as a shared resource that sits partly in your skull and partly in the tools you rely on. A teenager's experiment is a small illustration of how easy it is to move those sliders. Give someone a slightly different acoustic envelope and their test score shifts. Multiply that by all the cues and feedback channels in a modern interface, and you start to see why so many of us feel like we’re debugging our own minds.

Bottom line: it's a bit dull, but probably right. Treat your auditory environment like cognitive infrastructure. When the work is demanding, pick sounds that have structure but don’t tell a story. If you want to wander mentally, go with a lush soundtrack and let your brain’s predictive machinery run. And when a product promises focus, ask a simple, almost blunt question: focus on what exactly, and who benefits from it?

Meanwhile, teens will keep tossing stimuli at their friends and watching what happens. It isn’t just cute. It’s a reminder that you can run your own tuning experiments, one track and one task at a time, and maybe reclaim a bit of that parameter space before the apps finish claiming it for you.

Several sources explore how sound shapes focus and learning. A popular explainer argues that listening can boost attention, while peer reviewed papers from PMC5694826, PMC8448709, and PLOS One examine how auditory stimuli and binaural beats affect brain activity and performance. An EEG study from the Center for Brain Health adds nuance about how stimulation changes neural patterns; ScienceAlert reports a caution that binaural beats could actually hinder learning. Taken together, the findings are mixed and seem to depend on the task, the listener, and the specific sounds used.

Comments ()